By José Sarmiento-Hinojosa

Part child play, part reflection on the memory of the material, the work of Jodie Mack is a unique feature of evolving strategies that mix the structural, the game (in its performative sense), and the archive in a complex web of significations and semiotic rapports between the world, in its materiality and the eye of cinema. From textiles, jewelry, to the decomposition of light and travel movies, her work latches into the craft world of the quotidian to deliver us with a fantastic cornucopia of richness. We talked to Jodie about her beginnings in film, her intentions behind her wonderful film games, labor, grids, technology, glitches and much more.

Desistfilm: I think my first question would be, how did you start in the world of filmmaking? How you came around experimental cinema?

Jodie Mack: I think my interest in cinema came out of my interest in the theatre. First as a performer and then as a student of the history of playwriting and directing, which then led me to become interested in film studies. So, I thought I might write about cinema and then ended up in an experimental filmmaking class and thought that it could be something that could combine all the disciplines… I remember getting really excited in school watching films like Ghosts Before Breakfast or A Man With a Movie Camera, and just images of theater production – how early cinema was such an extension of the theatre. It always was the theatre for me, I think.

Desistfilm: So, when did you decide that animation was your thing?

Jodie Mack: Well, I think that generally, the type of experimental cinema that I learned about very early on was, of course, camera-less filmmaking, because I was in a school that didn’t have many cameras. We were doing film production within a film studies department, so nothing too flashy on the production level – just doing things pretty DIY, working camera-less-ly, which of course, can be defined as a type of animation in itself. That really, I think, grounded my interest in filmmaking through the lenses of different materials – like the relationship to the plastic arts, or also to commodities – things that you can use to make images on the film. That became a central concern.

Desistfilm: The Grand Bizarre is your first feature film. It’s sort of a mixed venture into travelogue filmmaking and your usual work with materials. How do you put together the semiotic significance of your materials alongside this aspect of travel? What’s the relation between them?

Jodie Mack: You know, The Grand Bizarre – it’s such a crazy form and huge project that… I basically had to make certain decisions to make it move forward. Of course, the idea of the travelogue became very important. Again, I thought about early cinema, about cinema’s relationship to the sewing machine, about the cinema’s relationship to train travel, and the development of ground travel which then became a development in sea travel, or air travel, and how the cinema became a sort of portal to take you somewhere else (something which of course has been disseminated and seen through many ways now, especially when we’re on the internet, this idea of not needing to actually move physically but still being able to go somewhere) was at the project’s core.

Something else I thought about were simulation rides; I remember experiencing them in the early nineties. And, you would go into a thing, and the seats would move too. And you were on an “adventure,” on a “safari,” you’re flying out in space… And of course this is all related to where we are now with virtual reality, this idea of a portal into somewhere else. This portal for me has always been in the rectangle of in the proscenium of the theater or of the church, or of the cinema, and of course it’s a sort of a flat plane but it’s also becoming more peripheral now, technologically. I wanted to be able to take the viewer into different physical places and to different dimensions and to be able to, in some ways, use the idea of close-up textiles as stand-ins for things like birds-eye views, views of landscapes (or straight ahead views of landscapes). And, I wanted to make this connection between an impulse to represent reality (or to mirror reality, a notion of mimicry and diegesis…) Is good art a great rendering of something? Or, does it create an essence? I wanted to prod at these unanswered questions, the ones present no matter the technology that develops, if that makes sense.

Desistfilm: Hoarders Without Borders and many other films you do remind me of a sort of “catalogue cinema” in the likes of Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi’s Ghiro Ghiro Tondo (2007), where they shoot these very old toys from the time of Franco’s dictatorship. Those toys symbolize the physical reality of what meant to be alive in the times of Fascism. Sometimes the archival images might seem innocuous in a way, but they are quite complex since they present a complete allegorical meaning in themselves. When you work with materials, what are your expectations regarding what should be the underlying narrative behind them?

Jodie Mack: I think the approach to the material changes depending on each different film that’s at hand. For example, The Grand Bizarre is kind of a culmination of a lot of these different, shorter “fabric films”, which started out as personal inventories. The first couple of them started while I was moving actually, and they were a record of everything I owned: the stripe patterns, the flower patterns… And, then gradually I started working with other people to borrow their collections and gained a reputation for being into collections and stuff. And, people would send me things. For example for my film New Fancy Foils, I made that film with a collection of these sample books owned by the animator George Griffin. He sent them on the mail and said: “I know that there’s a film here for you one day”.

Then of course, in The Grand Bizarre, I moved into things like textile archives, which presented the question of what to do with ancient textiles – you can’t work with them, you know, you shouldn’t really touch them, they could fall apart; you might not be able to get access to them… It’s much easier to get a digital copy of it. And, also, the minute that you enter a textile archive, you enter all these questions like: “Who owns these textiles?” Where were they made vs. where are they being exhibited and who has collected (and potentially edited) the information on them?

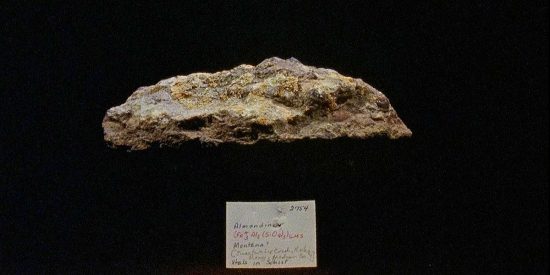

That then led me to something like Hoarders without Borders. I feel like that was the first piece I made with a formal collection. This was a physical donation from one person, Mary Johnson, to the Harvard University Mineralogical and Geological Museum. Because of that, I had no choice in the order that I could shoot it. That’s another thing that emerges from all the different inventories or quasi-inventories that I might do: rules of organizational systems (in this case: geological sciences). When I make a film with paisley patterns from around the house or something like that: I get to decide how things are arranged in different ways throughout the film in chronological order, in order of size and color, or things like that. So, in many ways my goals with each of these things just give each material a new life, a movement in a way that’s sort of fluid and open, and allows it to have a new voice through photokineticism or something like that.

Desistfilm: There’s a course of thought that comes around when looking at your images: Some of your films where the materials you’re filming are part of a process of labor. This can go all the way back to make us think about the methods of production: who’s making these fabrics?, for example, or thinking about the process of capitalist production, and stuff like that. And I was wondering if you think the playful nature of your work could be seen as something non-threatening behind the underlying deep strata of it all?

Jodie Mack: I think that my films are carrying a lot of weight of the animated film and the handmade film in general. They can be seen as playful, colorful or fast moving, and they are also posing a duality between the relationships with the product: whether one is critical of it or seduced by it. It’s like where we’re critical of the labor practices that go into making our clothes by tackling our process of buying our clothes and buying our bed sheets. Allowing for this duality or this duplicity of perception on the viewer’s part is at once freeing, but it’s also a risk, because you want the film to be taken seriously.

But, I don’t actually believe that the experimental context or art context is actually the place to have the discussion about capitalism and objects. This history has hands that are so covered in blood, it’s also like: the revolution is never happening here. So, I also want to reject a mode of seriousness or pretention that is feared by the worker, in the language of experimental film, where so much of contemporary art and experimental film is seen and made for elite circles with a lot of education. I think at this point we need to really consider the notion of accessibility as a way of getting different circles excited about the possibilities of these types of cinema.

Desistfilm: Wasteland No. 1: Ardent, Verdant, its structural game, deals with computer boards and nature. There’s a strange relation between the materials. It’s like technology seems to exist to be discarded while nature remains alive and present, which kind of reminds us of our own relationship with nature. Is that something you were thinking about when you made that film?

Jodie Mack: Well, I was definitely interested in not only the dissonance between nature and technology, but also a notion that technology is often designed with nature as an inspiration, or the idea of human infiltrated nature as inspiration, such as the idea of render farm. But of course, even the mapping of a farm isn’t natural; it incorporates grids into the plantings and planning.

Another thing that interested me in that film is the collision of space and point of view as a sort of carry-over in the relation that I saw between images in The Grand Bizarre – of course, these computer chips started to look like cities from outside the plane, and Google Earth, or Google Maps, this technology with birds-eye view vs. the images from the landscapes at straight-ahead view. There’s this temporal collision of these two vantage points, which becomes really central to the film’s pulse. And I don’t know what it says about our involvement with technology. We’re definitely all tied up here.

Desistfilm: Let Your Light Shine is a sort of treaty of light in three-dimensional space. What made you approach this work as an expanded cinema project, with the prismatic glasses and everything?

Jodie Mack: When I made that film, it was to go along with another film that I made called Dusty Stacks of Mom, which uses the album The Dark Side of The Moon as a structure. The cover of the album is this prism, and within the film I was making this parallel between how light functions in scientific exploration and also in kitsch-hippie lava lamp commodity culture, and so I used some of the filters for that film.

Then, I ended up getting some glasses. First I did some tests by using them and watching things like the Studies One through Five by Oskar Fischinger, from the 20’s or 30’s, and Free Radicals by Len Lye because, of course, they’re white on black and it separates white light into the colors of the spectrum. So, I was just hoping to create this sort of fireworks show within a program of five films that I was designing as a rock concert, and this was supposed to be the final encore. Of course, because I’m also interested in the idea of everyone’s response to natural phenomenon of group spectacle, which is, again, this idea of flatness or proscenium being a portal, things like groups of people watching the sunset, or watching fireworks, are something that are very interesting to me: to see how abstraction is allowed to permeate into a mainstream culture.

So yeah, that was my impulse, really, was just to try it out. I would like to actually try to go back to that technique in some point, but it might take a few more projects until then.

Desistfilm: So about Glitch Envy, I think it is particularly remarkable how it fuses together the notion of recreating the image glitch which is in this different material, like junk mail you know, in this process of marrying the old media with the new. So I was wondering if you would eventually consider working with digital media instead of physical one, and what would you think would be the immediate connotations of that?

Jodie Mack: To go back to the sort of thread going on through the questions about the Wasteland film and some things between The Grand Bizarre, Glitch Envy adopts the idea of the quadrant, making images in squares in the digital world as opposed to making images in grains in the analog world – this idea of creating curves on grids and things like that. Also, it considers ideas surrounding the development of technology and how they don’t answer new questions: sort of the same things happening over and over again.

At that time there was so much attention for new media and glitch… But I didn’t really see glitch as doing anything that new from camera-less films, because they’re all about making incisions in the material, and treating the material as a canvas, and things like that. But different digital experiments have made it into some of my films. So, for example, there’s some datamoshing within Dusty Stacks of Mom, and there’s some sounds created with numbers going on in The Grand Bizarre and some sort of using some images of maps as sounds and things like that. So I’m definitely addressing in it the relationship… I was thinking about doing something in VR the other day just for fun, or maybe just start to experiment with 3D, you know, just to experiment, so yeah, that can definitely be in the horizon.

Desistfilm: The idea of arts and crafts is constantly present throughout your films, so when you present your materials in the context of your work, they acquire certain artistic quality, which might or might now be there before being put there in the film. How do you approach this? What are your thoughts in the underlying value of crafting?

Jodie Mack: I don’t necessarily see a division between objects that circle between craft circles or fine art circles, and we’ve really had that lack of distinction for a really long time. I really do think it’s a matter of context and that the definitions to what and how we ascribe cultural or financial value to these objects is extremely suspect, especially given this historical cycling that you can see between some different sorts of crafts or trajectories or fine arts trajectories.

So yeah, I don’t necessarily see the distinction. But perhaps one of the distinctions is that often times the same sort of objects – whether they are commodities, hand-made crafts, or works within galleries – in the fine arts context they’re more likely to be written about in the context of media cultural theory in our history. But, again, that’s sort of one of the roadblocks that I see between being able to connect elite fine arts and mainstream circles. The worker needs to understand the labor pamphlets that you’re passing out when you’re creating your union, and there’s such a discrepancy in education across society. So, the worlds can’t talk to each other.

Desistfilm: I want to talk about sound in your film, which plays such an integral part. How do you go about conceptualizing the idea of sound in your films, how does process occur?

Jodie Mack: Well, the sound definitely works in different ways for different films, I have an interest in the idea of indexical relationships between images and sounds, so I’ve made different films where the images are the soundtrack, or made the soundtrack with images. A lot of my longer films borrow from the musical form. I made some sort of original show-tunes-y musical; I used an existing album as a structure for a film. I just made my most recent film as another sort of album-based practice, so the idea in music is always present, mostly because I was always very interested in one point in the history of experimental animation in visual music, these analogies between hearing and seeing and this sorts of visualizations between images and sound, which of course now have many more possibilities with the digital world, the digital arena. I’m also very interested in the role of the “number” within cinema and how it creates a double suspension of disbelief, because usually you’re there for the movie but once when the music starts it allows you to go one step further, and obviously of course, the relationship between what is a fine art film and what is a music video or an advertisement, because of course music videos and advertising both borrow language from historical experimental film, so again there’s sort of less of a distinction between what is what, because it’s already been digested by the industry, a lot of this early avant-garde editing or shooting techniques.

Desistfilm: And what about the performative aspect of some of the projects you’ve worked in? You’ve worked with some form of expanded cinema before. Would that be something that you would be interested to repeat?

Jodie Mack: Yeah, I have a couple of films that include performative aspects. My film Unsubscribe N°4 it used to have a live singing soundtrack and then a live speaking thing in the cinema, and my film The Future is Bright incorporated live singers at times. The glitch film that you mentioned incorporates the audience making the sounds of computers and also testing out different ringtones on their phones. And then of course Dusty Stacks of Mom had a live soundtrack… The cinema is a place where viewers just sort of zip-up and remain quiet, but I like to invite the viewer and activate their body to add to the experience.

I’m interested in creating a one of a kind experience, again with my interest in theater, and how every performance has an ephemeral quality and how can be different every time. I also want to fight against this notion of cinema as a reproducible object, which of course it sort of has failed in many cases of surviving in an art world context, because it is a reproducible thing instead of a one of a kind artwork. I’m pushing against the need of something to be lucrative in order for it to happen and be in the world in favor of an artisanal approach.

Desistfilm: So which projects are you working in now?

Jodie Mack: Well, right now I’m spending a lot of time with the administration of The Grand Bizarre, so there’s a lot of travelling and working on new lectures and workshops for different schools or festivals while I go around. But I’m also working on this series of sculptures, spherical zoetropes…

[Gets up and brings an spherical object]

So this is one of them, they’re basically just for right now, they’re basketballs that are covered in wax, so I’ve just been dripping crayons on to them and then they spin on a record player with a strobe light and animate. I’m working in some of these. I’m actually working also in an installation version of The Grand Bizarre that is going to be shown at the Jeonju Festival in Korea, so we’re separating different moments that didn’t make it into the film and making a gallery, sculptural thing… And I’m shooting a few more films and working on another couple of Hoarders Without Borders and also something more extended… But I’m also just taking the time to relax a little bit and starting to teach again for the first time in a while, so I’m preparing new classes, just wrote a class about time based recording and nature, something about underwater photography and recording wind, just stuff like that.