By Jay Kuehner

Gorria (2020), a short film by Basque artist and visual anthropologist Maddi Barber about the life-and-work-cycle of rural livestock and their handlers in Arce-Artzibar, Navarra, features an arresting concluding shot. In it a shepherd is seen, waist down, harnessing a lone sheep, with one bandaged hand resting on its brow, in the other a crook fashioned from a branch. They wait, poised on an unknown threshold, foregrounded in the landscape. The posture evokes a sense of defiance, pride, affection and a bit of vulnerability, as the filmmaker distills within a single shot the uncertain liminal space between animal and human. For a film that begins with the slaughter of a sheep, the finale feels mercifully tender, hopeful even.

The film was the winner of Punto de Vista’s 2019 edition Proyecto X Films (a production project of the festival to develop films of “singular artistic interest”). As you sow, so shall you reap: the 2025 edition saw the return of Barber, collaborating with fellow Basque filmmaker Marina Lameiro, on the medium length experimental documentary Cambium, set again in nearby Lakabe, the once-abandoned and now thriving exemplary eco-village. More diffuse and willfully ambiguous than Gorria, Cambium is no less site specific, homing in on a specific ecosystem and habitat of ‘Paraiso’, a forested community on the threshold of change. Foresters arrive with their terrestrial scanners, followed by loggers with their feller bunchers: what appears an act of destruction is in fact a paradoxical project of restoration, an attempt to reclaim arable land from the mandated government forestation of the 1960s.

While much of the film is shot in a putatively ethnographic, observational style on 16mm, Barber and Lameiro channel an oneiric, animistic essence of the forest canopy, employing the light scanning technology (not unlike artist Mathilde Lavenne’s ‘phantom mapping’ of a Mexican farm in Tropics) toward a more spectral consideration of territory, coupling the ghostly pine hollows with the voiceover of a nameless medium who communes with the trees. In one telling sequence the trees reveal that it is they who “already know how to take care of eachother”, and it is the humans who have arrived here that are still learning to do that. Between the contrasting realms of metaphysical entreaty and mechanical incursion, the simple exposition of children at play in the woodland – seen camping, cooking potatoes in the pine embers, applying fluorescent face paint at nightfall – offers a more innocent, unmediated perspective.

Drawing these spheres together syncretically, rather than dialectically, is instrumental to the film’s beguiling mystery. A montage of concentric tree stumps suggests a kind of cinematic equivalence to dendrochronology, the study of growth rings to include human as well as natural history. The film seems to be tacitly inquiring: Is there a form of social and cultural cambium – an active tissue that ensures the healthy secondary growth at the roots of a community? It is difficult to parse if the film is sympathetic to the project of reclamation in its seeming ‘attack’ on the land; if the desired end goal of this community supersedes its establishing means? The film leaves this tantalizingly open. Cambium would win the Special Audience Award, in part owing to its sheer cultural and natural proximity to the festival, but one would hope too on account of its clear artistic merit.

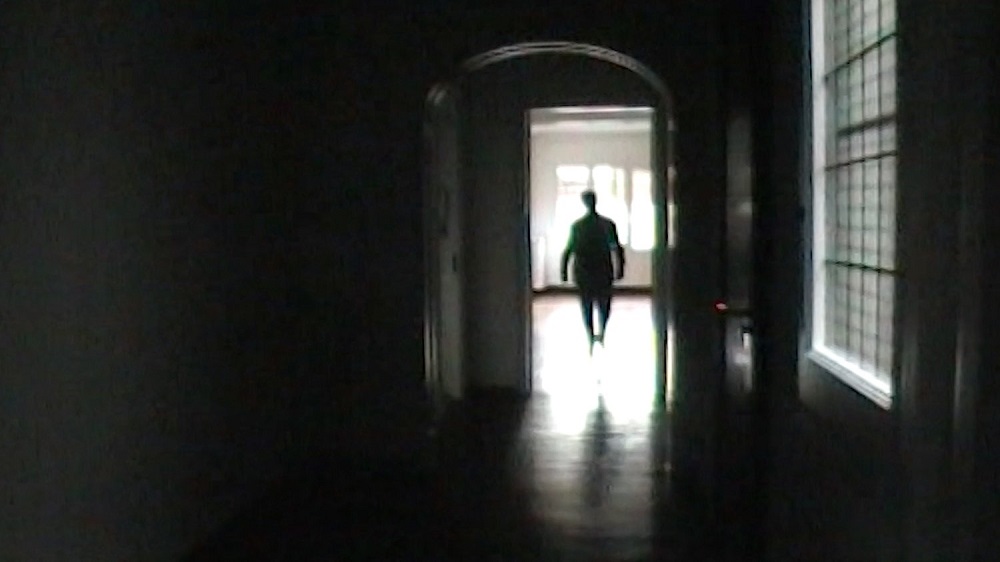

Another cryptic entry from Spain garnered a Special Jury mention: Ramon Balcells’ short A. is in some ways a spiritual descendant of Pere Portabella’s Mudanza (2008) (featuring the removal of furniture and artifacts from the home of poet Federico Garcia Lorca ), except here the furniture has already been removed, and only voices – emanating from memory? – remain. A son returns to the home of his deceased grandmother, panning through the empty corridors and blank walls, a resounding silence punctured by the sound of footfall on creaky floorboards from an unnamed custodian roaming the space. Fragments of domestic conversation are conjured from the past; vaguely audible, lighthearted among women, yet seemingly embedded in the walls themselves. The sense of amnesiac drift is palpable, of a grandmother losing her memory, of a son trying to remember. Balcells, his reflection caught in a chamber mirror, camera raised, has fashioned an evacuated tango: ode to a once young dreamer returning to a house now overcome with a deep and cruel silence (“Hay en la casa un hondo y cruel silencio huraño” are the lyrics of Enrique Cadicamo, who’s invoked in the film’s prologue).

The sorrow of exile is built into the very architecture of A While at the Border, Ileana Dell’Unti’s epistolic portrait of two sisters whose lives are cleaved apart during the advent of the Argentine military dictatorship; one, Claudia, fleeing for Sweden (having escaped via Uruguay); the other, Julia, remaining in the north of Argentina. The kidnap and torture of the former, briefly alluded to in the film’s prologue, is the haunting factor in an otherwise mundane exposition – integral to the film’s contrapuntal formal design – of various public spaces that ‘backdrop’ an exchange of voiced letters between the sisters, now a world apart. Thus the film is sounded as much as seen, letters read aloud by actors inhabiting the roles of Claudia and Julia, a technique of distanciation that paradoxically achieves a form of historical intimacy: how does a legacy of repression become embodied by future generations? As a story about the director’s own familial migrations, it is all the more personal in its structural composure.

Certain juxtapositions of Swedish and South American urban space – escalators, parks, plazas, libraries, and façades – speak to the thresholds of private and public space; concerns to both sisters who study and practice architecture, but also to the socio-political climates that ebbed globally in the late 20th century. Rather than an object lesson in the banality of evil, the film seems on some conceptual level to be invested in notions of reterritorialization apropos of Deleuze and Guattari: what are the new ‘codes’ by which Claudia in particular acclimatizes? Where does memory reside in relation to internal and external space? At over two hours, the thesis has a proclivity toward the willfully static, yet it is the gravity of the correspondence that propels the film into more conventional but satisfying storytelling: of a love and respect among sisters told through the nuance of the quotidian.

Gravitas through mundanity, if not absurdity: such was the ethos of Irish writer Samuel Beckett, which is mined by fellow Dubliner Declan Clarke in commensurately minimal and melancholy style in If I Fall, Don’t Pick Me Up. Clarke takes Beckett’s sojourns to Germany in the 1970s as a point of inception, where he developed a working relationship with theater director Walter Asmus that would continue until the writer’s death (and manifest posthumously). Absent any archival footage or staged productions, the film is epistolary by design, drawn from the collaborator’s terse yet respectful correspondence, as well as production notes the two shared. Clarke, shooting on 16mm, lingers in the empty spaces vacated by Beckett’s habitual peregrinations, the parks and cafés he frequented on his curious German sabbaticals. We wait, all too appropriately, for something to happen. But Clarke has transformed the urban landscape into a stage of sorts, where durational static shots stand in for Beckett’s lean existential grammar, where the slightest disclosures accrue into something revelatory (the banal interior of the now vanished Giraffe restaurant where Beckett ritually dined takes on the muted sorrow of absence). The frustrations of waiting become a mild form of pleasure, and Clarke has notched yet another unpolished gem in his formidable oeuvre.

An entire entry could be devoted to the festival Grand Prize winner Cuadro negro, by José Luis Sepúlveda and Carolina Adriazola, who’ve endeavored to create an arid hybrid in which a young woman filmmaker is tasked with making an improbably artistic documentary about the Chilean army. The film pulls off a satirical construct so weighted, with a tone so dry, that it plays like an straight-faced observational doc, the lone director barking orders at taciturn soldiers (low crawling absurdly through the fieldgrass, or galloping with valiant intent on horseback in and out of frame upon a vast desert landscape). But it is in the starkly contrasting domestic tableaux – the director having moved back home to live with her grandmother – where personal and political histories entwine most caustically.

Festival Artistic Director Manuel Asín could bow out with pride, having fulfilled his four year tenure, maintaining the festival’s resistance to orthodoxy and a persistently liberal conception of nonfiction. His parting gift was nothing less than a retrospective devoted to the Dutch painter/filmmaker Frans van de Staak, whose very experiments with film grammar – employing poetry, theatrical performance, philosophical essay, and narrative feints – could be seen as a precursor to the festival’s own reflexive ethos. Said Van de Staak: “I leave out the why as well as the results. What’s left is the moment of endeavor.”