Photo: Alexis Dahan

By Julian Ross

Found footage has its romantic connotations. It suggests an archeological unearthing or a rescue effort – the artist as savior. As twilight falls on film as material, this image has been intensified. The lost orphan films must find a home before chemical degradation renders them lifeless forever. I think of poetic associations on youth and loss made in Jay Rosenblatt’s films or the resurrections of everyday life in colonial-era Indonesia in the films of Péter Forgács and Gustav Deutsch. There’s the other side of “found footage” filmmaking, of course, that takes on a far less precious approach to its discoveries. An approach that sees discarded film as junk or raw material in ways that, if I were lost film, maybe I’d rather stayed buried in oblivion. I think of Luther Price whose recent Garden series has involved scratching and painting onto abandoned films, which are left to rot as compost in his backyard. I’m also reminded Aldo Tambellini’s early films where film material was treated to all sorts of physical and chemical alterations, painted in his trademark black. We might consider the former approach to be more respectful to the original footage; yet, on the other hand, the latter, in its own ways, respects the material for what discarded film is in the way it doesn’t pretend the lost films are anything but disposed scrap.

Photodocumentation of Bunri sareta firumu (Film Divided Apart, 1972).

Scanned from Imai, 2001, p. 119.

When artist Norio Imai collected film from the cutting room floor of a local television production, the latter approach was the one he took for his contribution to Japan’s first group exhibition of film installations held at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art in 14-19 October 1972. For Bunri sareta firumu (Film Divided Apart, 1972), Imai’s take on found footage was distinctly material with an emphasis placed on film as object. He further spliced a selection of the films into individual frames that were projected in rotation as slides. Not only the photographed image but also the film material itself became part of the projected image in the slideshow display. On the floor next to the slide projector, Imai piled the rest of the discarded film material into a mountain as if they had been left abandoned, once again. Imai’s emphasis on material in his approach to “found footage” recalls his first film En (Circle, 1967), a simple short film that shows a flickering circle in the centre of the screen resulting from holes that Imia had hole-punched into a black film leader. The film recalls the use of the hole-punch by Takahiko Iimura and Natsuyuki Nakanishi’s On Eye Rape (1963), where an abandoned educational film found by Nakanishi in a dustbin was transformed into a commentary on censorship by the two artists who hole-punched the material in imitation of censorship against pornographic material.

Imai was not alone in his approach to film as material in the group exhibition of film installations. Alternatively titled Expression in Film ’72 – Thing.Place.Time.Space –, the exhibition Equivalent Cinema was the fifth in an annual series held in Kyoto as the Exhibition of Contemporary Plastic Arts (Gendai no Zokei). As its title suggests, the series didn’t initially start as a presentation of cinema but, instead, as an outdoor group sculpture exhibition in 1968. In recognition of the turn towards filmmaking demonstrated by the young local sculptors, the exhibition became a film screening held in a conference hall for its third and fourth edition. By the early 1970s, however, the local artists had begun to explore film beyond the cinema frame demanding alternatives from the cinema space with their performances and expanded projections. ZONE, held at the Mainichi Shimbun (Newspaper) Branch Office 3rd Floor Hall on the 8th, 14th and 19th November 1968, for example, presented multiple-projections and performative expanded cinema by local artist Shoji Matsumoto and Tokyo artists Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver and Rikuro Miyai together with demonstrations of electronic music and Butoh dance. By the time Equivalent Cinema was held in 1972, the artists began to incorporate their background in sculpture into their interpretation of film expression, resulting in an emergence of film installations in the area. Although Imai was the only one to use discarded film in Equivalent Cinema, his take on found footage derived from being a part of this community of artists.

Exhibition view at ‘Perspective in White’. Courtesy Galerie Richard, New York.

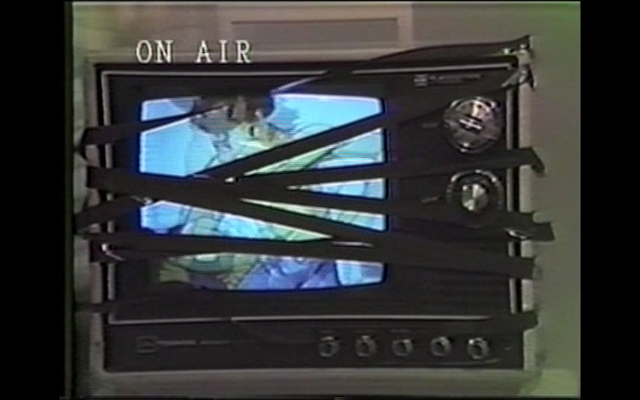

Imai’s approach to the canvas in his early work also prepared him to pull film off the wall as image and force it into the museum space as sculpture. At his 1966 solo exhibition ‘Imai Norio: Space of White 1964-66’ at Galerie 16, Kyoto, Imai presented a series of works on white where he pulled cotton cloth over metal moulds. These works, some of which are currently on show at Galerie Richard, New York, appeared as if canvases were bulging out from the walls in an attempt to become sculptures. At the same gallery in Kyoto a few years later, Imai acted out a similar transformation of the canvas for the cinema screen. Complaining that ‘although the projected film changes, the screen always remains the same,’ he installed a dome screen for the exhibition ‘Image Speaks!’ (Eizo wa hatsugen suru!) on 12-19th January 1969 where every couple of hours multiple projectors were used for a series of expanded cinema presentations by Shoji Matsumoto, Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver and Rikuro Miyai. Later in the 70s as he began working with video, Imai recycled the interpretation of discarded film as material by rolling out open-reel videotape to bandage a television monitor until the image broadcast became invisible in On Air (1980), staged at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art and Nagoya’s Box Gallery, and to cover the walls of a room in Kukei no Jikan (Time in Rectangle, 1980), staged at Kobe’s Gallery Kitano Circus. Documentation of both is available to see as part of his Digest of Video Performance, 1978-1983 in EAI’s DVD release Vital Signals.

Screenshot from Digest of Video Performance, 1978-1983

Entering the art establishment did not necessarily mean an elevation of status for the discarded film used for Film Divided Apart and its subsequent treatment by Imai was no less destructive. In the following year at the Kyoto Biennial in August 1973, Imai spliced together the same footage into one stream of seemingly random fragments comprised of news and television media as Jointed Film (1973). For the Kyoto Independents Exhibition earlier in the year in February 1973, Imai used the found footage as props for a performance where he spliced together the disparate films in front of an audience, the results of which were left on display. After all, Imai is a child of Gutai whom he joined as its youngest member in 1965, a group based in Osaka that, among a range of activities, pursued creative expression through use of discarded material and interpret the creation of art as an opportunity for performance. As early as 1957, its members famously staged what has been described as “performance paintings” for their event Gutai Art on the Stage in front of seated audiences. Shozo Shimamoto’s film Sakuhin (Work, 1958), exhibited as part of the recent retrospective exhibition Gutai: Splendid Playground at the Guggenheim, demonstrates that experiments in film existed in Gutai long before Imai had joined. For the film, Shimamoto obscured the photographic image with layers of paint, perhaps the first use of found footage in Japanese experimental film.

Norio Imai’s first New York solo exhibition ‘Perspective in White’ is currently on show at Galerie Richard, New York, until 29th March 2014.

http://www.galerierichard.com/com_presse_artiste.php?lang=en&id=129

Reference:

Imai, Norio (2001). Shiro kara hajimaru: Watashi no Bijutsu N?to (Starting from White: Notes on My Art). Osaka: Brain Center.